Time flies, but this morning it seems stopped. The leaves on the vines that surround my parents’ house is my best indication that summer is fading toward fall. They rustle gently with a windy chill in the air that wasn’t here yesterday. I treasure the slowing of time in this moment – so much has passed away. Many of the things people cling to have been slipping from my grasp this summer. The change of the leaves is a physical mirror for what’s happening in our lives: leaving behind a life, taking leave from work, and moving on to our next season.

We’ve finished our assignment in Sri Lanka. The back to school emails we receive from the Overseas School of Colombo are another reminder that our kids won’t be going back there for school. And they add yet another administrative task to the bewildering list that develops when you leave behind an entire life.

It’s been a month and 11 days since we boarded a plane at the Colombo airport. Our previous life in Colombo is fading quickly into a series of misty memories. Talking about our experience helps solidify our long-term recollections. But quick family reunions and passing meetings with friends aren’t really the place for that. We keep reminding ourselves that while we’ve been overseas, our friends and family have also been living, losing, loving, and having adventures of their own here at home. Inevitably, the tragedy of our fading memories quietly continues.

I’ve left behind the work to which I was so committed. I keep watching to see evidence of the progress of my projects: trade deals, large energy sales, cybersecurity legislation, and the like. But now I watch as an interested observer. I’m no longer a participant. Letting go of the work has been hard for me – one of the downsides of being passionate about your work. My colleagues in Colombo have graciously left me out of the loop, either trusting to the notes I left behind for them or figuring out their own new vision for the way forward. We work in a reality of ever-changing team members, and we adapt by working with whoever happens to be present. I miss being present with my work friends and contacts in the same way that my children must be missing their school classmates.

For better and worse, though, we’ve left that life. Driving to the airport late at night with an embassy colleague to see us off, we boarded a plane for Singapore. We spent three days in that fascinating and magical city, fulfilling my long-waited dream of sharing Singapore with my family. It was everything I’d hoped for. It was life-giving. It was expensive. It’s wasn’t long enough. There were lots of surprises.

In Singapore, we connected with old friends and made new ones. We played rock and roll at our good friend Tony’s music studio and met Qing Lun, a master of the Chinese flute. He was gracious enough to invite us to a rehearsal of his traditional Chinese folk music orchestra. Somewhere in the middle, we played a mixed rock/flute version of Hotel California. It was unexpected, it was beautiful, and it was a moment that I never wanted to leave.

We landed in America on the 4th of July. My parents killed the fatted calf, which in modern times meant a trip from San Francisco International Airport directly to In-And-Out Burger. They have continued the full prodigal son treatment for the entire summer, opening their vineyard-surrounded ranch estate to us. They have cooked for us, given us free access to their vehicles, taken us camping at Lake Tahoe, and made lifelong memories with our children. They’ve put up with us for far too long as we comply with our congressionally-mandated home leave between overseas assignments.

We attended the kids’ first American pro baseball game (go Angels!) and spent a week in Disneyland before leaving to spend our home leave in central and northern California.

My grandmother, Vinita Mae (Coulter) Shinn, had her own departure this summer. We had a chance to have one last conversation with her before she took her leave. My parents, in addition to hosting us, have been planning her funeral and starting to deal with her effects. We’ve missed the death of several treasured relatives while we’ve been overseas. It was a special grace to be with her in her last days, and one we don’t take for granted.

Our leaving isn’t finished – soon we’ll leave California for a road trip across the United States. In addition to admiring the breadth of this great land, we’re stopping to see friends we’ve left behind. The fact that we can pick up where we left off with so many of our friends gives me hope that we’ll keep some connection to those we’ve left more recently. In a life with many leaves and few roots, these friends are critical tethers to what’s most important.

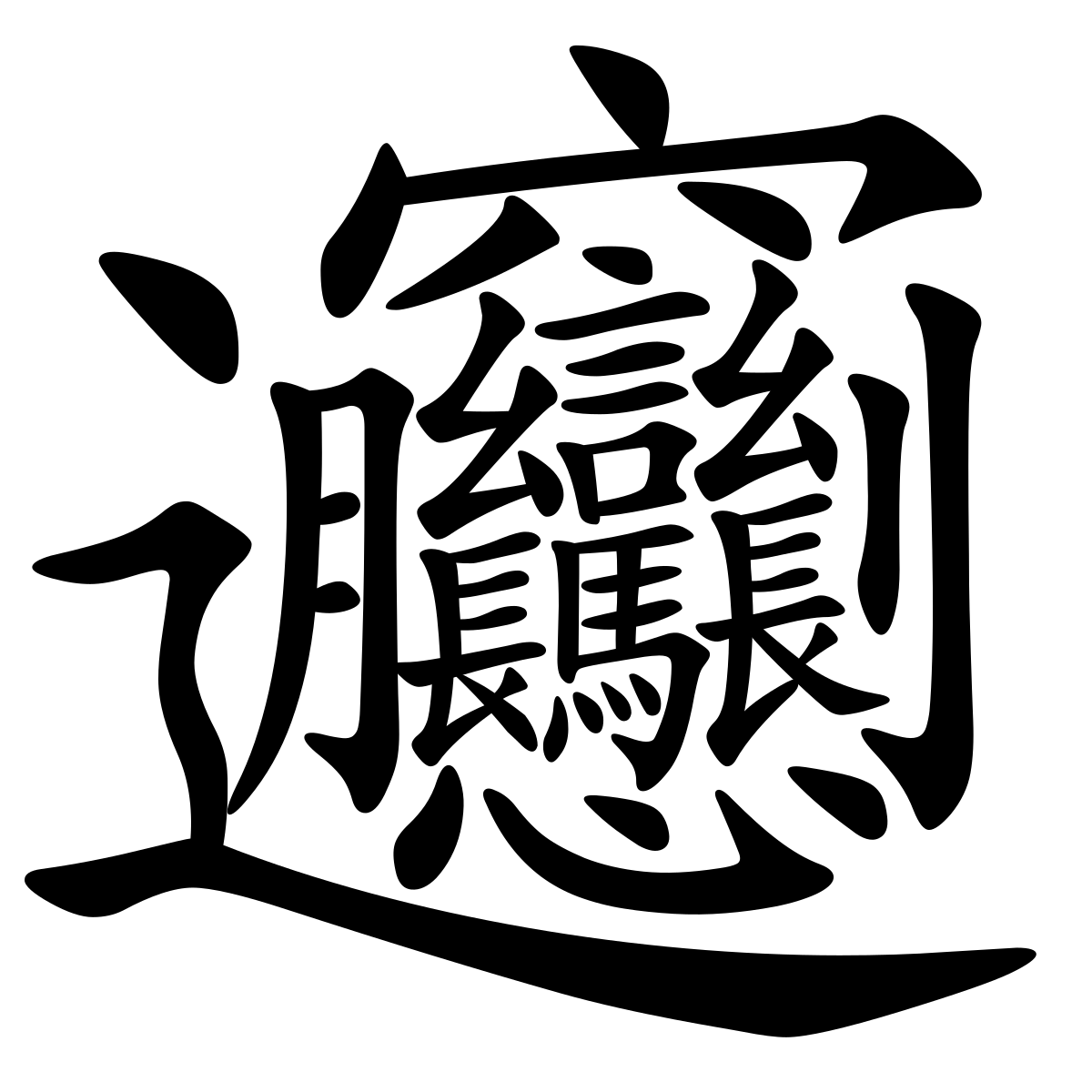

At the end of our journey this summer there will be an apartment in Arlington, Virginia with beds where we’ll be able to rest for most of a year. After sleeping at friends’ houses, on couches, in sleeping bags, and in hotel rooms, we’re all looking forward to staying put for a little longer. I’ll be studying Chinese at the Foreign Service Institute, which is now called the National Foreign Affairs Training Center (NFATC). Clara will attend high school, Lisa will homeschool Caleb and Joshua, and Liam will be taking online college classes and attempting to get into a university in Virginia. It will be a year of training and preparation for everyone as we prepare to leave for our next assignment, back in Beijing.

There’s a lot ahead of us. But for now, we’ll try to enjoy leave and the leaving summer and watch the vineyard leaves rustle in the wind that brings fall.